Chapter 1. Introduction

1.1. What are UK EPAs?

The Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) are comprehensive trade agreements between the United Kingdom (UK) and African, Caribbean and Pacific States (ACP). Their background dates from when the UK was a member of the European Union (EU). In an effort to update its prior trade relations with ACP countries, and ensure compliance with the rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the EU has negotiated and signed Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) with African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States (ACP). These include seven (7) EPAs with Central Africa, Eastern and Southern Africa (ESA), East African Community (EAC), Southern African Development Community (SADC), West Africa, Caribbean, and Pacific countries. The trade relations between the UK and ACP countries after it has left the EU are largely based on these EPAs.

EPAs are WTO-consistent trade agreements, but they go beyond conventional free trade agreements (FTAs) by focusing on ACP countries development, taking account of their socio-economic circumstances and including cooperation and assistance to help ACP countries implement the agreements. Not only do EPAs seek to foster favourable market access terms among parties, they consist of an integrated package of protocols on trade in goods, trade in services, investment, capacity development, administrative assistance, etc. Moreover, EPAs can enlarge their scope of coverage by introducing rendez-vous clauses where parties wish to continue negotiations on specific matters at a later stage.

To respond to ACP countries’ concerns, EPAs include specific asymmetries in their favour, such as the exclusion of sensitive products from liberalisation, long transition periods, flexible rules of origin (RoO), special agricultural safeguard measures, and food security and infant industry protection. EPAs are also designed to be drivers of change, which will help partner countries attract investment and boost economic growth through initiating reform and strengthening good economic governance [1] .

1.2. Trade with the UK from 2021

The UK withdrew from the EU on 31 January 2020, when the Withdrawal Agreement entered into force. Leaving the EU had important implications for the 79 ACP countries, not only for the bilateral relations between the EU and the UK. The post-Brexit EU-UK relationship largely determines the UK’s relations with third countries, and this inevitably creates certain disruptions and uncertainties, but also new opportunities if businesses know how to take advantage of the new situation.

The UK participates in a number of international treaties as a result of or relevant to its membership to the EU. These treaties underpin the UK’s relations with third countries and international organisations. During the transition period until the end of 2020 [2] , the UK continued trading under EU rules, while negotiating a new trade agreement with the EU. Now that the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) has been reached, the UK will be able to negotiate new trade deals with the rest of the world [3]

.

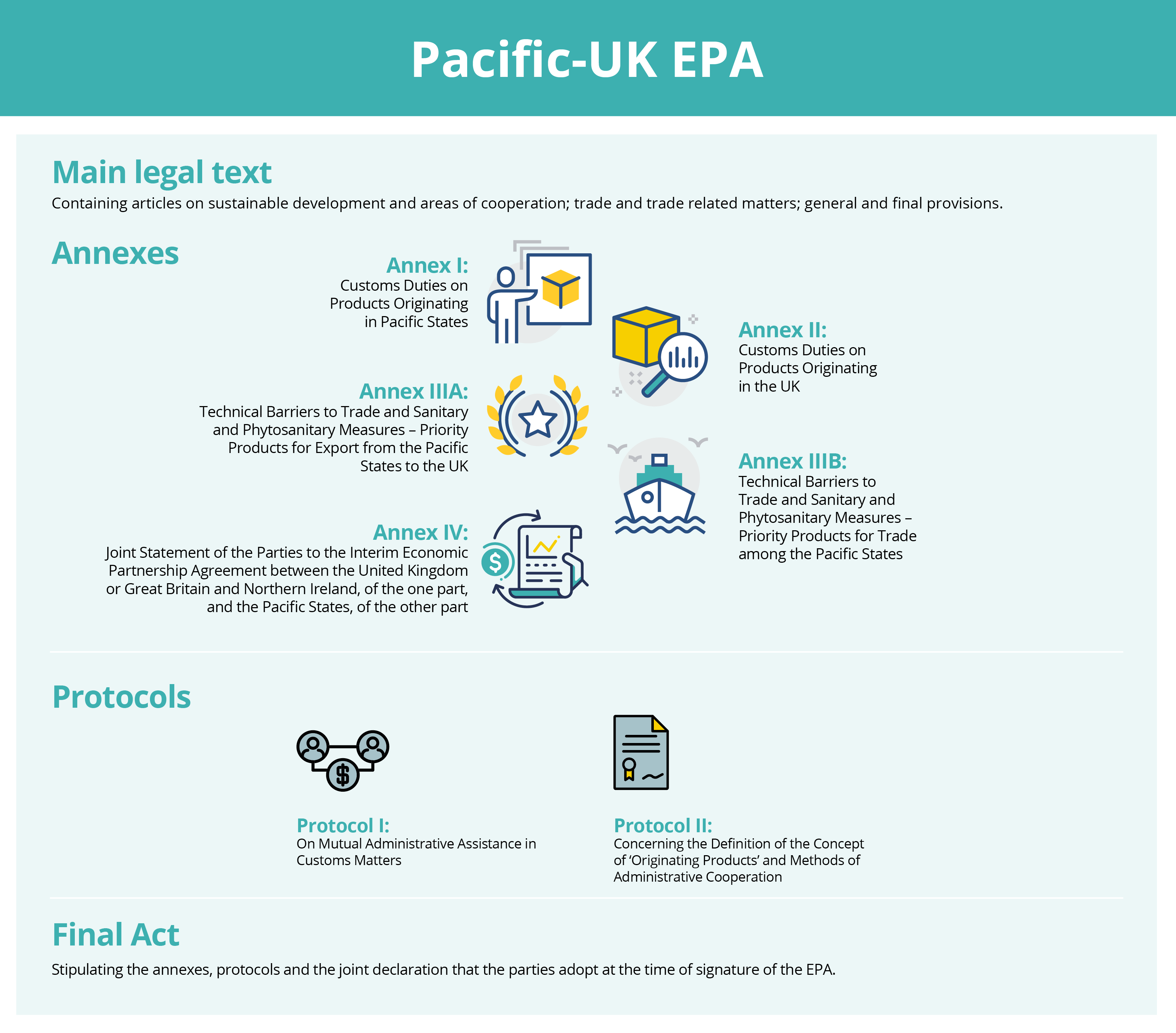

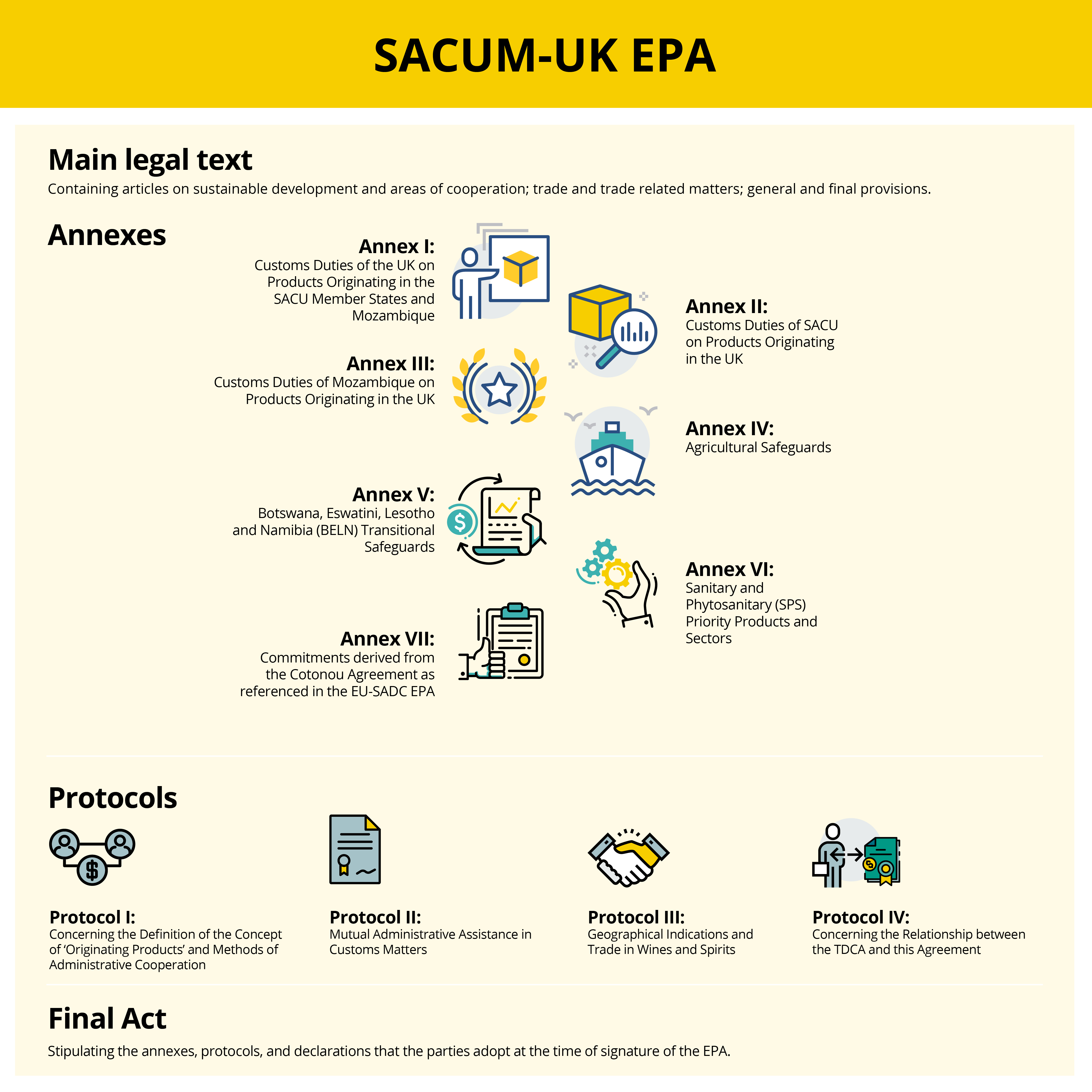

The EU’s EPAs with regional ACP groupings ceased to apply to the UK since December 31st 2020. The UK has, however, sought as far as possible to continue the effect of its current arrangements after it leaves the EU. In line with the British government’s commitments in the Trade Bill of 2018-2019 [4], the UK commits to continuing the trade relations with ACP countries. Therefore, it has signed continuity agreements with ACP states, including ESA, CARIFORUM states, Southern African Customs Union and Mozambique (SACUM), Pacific states, Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, and Kenya. The newly negotiated UK-ACP EPAs took effect since January 2021 [5]. Negotiations of an EPA with Ghana were finalised in early February 2021, and took effect soon after. Apart from continuity agreements that largely mirror EU-ACP EPAs, new UK-ACP negotiations are likely to take place in the long term.

To address potential disruptions and provide maximum stability for businesses, it has been agreed, for example, in the ESA-UK EPA, that the EU’s materials and processing can be counted towards the UK’s and ESA’s content should they meet the conditions for cumulation specified in the agreement’s protocol on RoO.

The British government has also taken other measures to avoid trade disruptions with ACP countries. One of the safeguards is the ‘Cross-Border Trade Act’ [6], which allows the UK to continue granting non-reciprocal market access to developing countries equivalent to the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP) and Everything-But-Arms (EBA) systems and includes an ‘LDCs services waiver’. Therefore, LDCs would experience little changes under UK’s EBA scheme [7]. ACP countries, particularly those who have not signed continuity or new EPAs with the UK, may continue making use of these alternatives.

Despite the changes and disruptions witnessed during 2020, new opportunities are presented in the UK-ACP EPA negotiations. The state of play in the negotiations and the current global economic context bring opportunities to improve relationships among EPA partners, particularly by updating and improving the content of these texts. Among a number of improvements that can be incorporated in these EPAs, UK-ACP EPAs may include safeguarding food security and industrialisation of ACP countries. Moreover, the UK-ACP EPAs are also more flexible, adequately monitored, and ideally fit into a broader trade and economic policy framework guided by poverty reduction objectives[8] .

Guidance on UK’s trade with developing countries during and after the transition period is found at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/trading-with-developing-nations-during-and-after-the-transition-period

1.3. UK EPAs’ key components and their roles

UK-ACP EPAs’ improved market access provisions are liberal, often asymmetrical, and include relatively flexible RoO that enable deeper integration into global value chains (GVCs). Some EPAs contain provisions on ‘new generation’ trade issues such as e-commerce and personal data protection, but also leave room for future negotiations.

Standard provisions on cross-border trade

EPAs’ chapters on trade contain all the standard provisions like elimination or reduction on customs duties, trade defence instruments and non-tariff measures (NTMs) that set the stage for market access liberalisation.

Addressing barriers to cross border trade is an integral component of EPAs as it relates to trade opportunities but also the UK’s economic development objectives. Freer cross border trade is generally considered mutually beneficial as it allows for wider consumer choice in the variety and quality of goods and services, lower prices through increased competition and efficiency, higher productivity, and higher real wages and living standards for the countries engaged[9].

Addressing barriers to cross border trade is an integral component of the EPAs as it relates to trade opportunities but also the UK’s and EU’s economic development objectives. Freer cross border trade is generally considered mutually beneficial as it allows for wider consumer choice in the variety and quality of goods and services, lower prices through increased competition and efficiency, higher productivity, and higher real wages and living standards for the countries engaged [10].

Asymmetrical liberalisation

To ensure that development objectives are fulfilled, the EPAs include asymmetrical liberalisation provisions in favour of ACP countries. This means most ACP countries immediately receive duty-free, quota-free (DFQF) access to the UK, while they are to guarantee gradual tariff reduction on imports from the UK. Furthermore, depending on several developmental criteria (like GDP per capita or HDI scores)[11], ACP states may not have to reciprocate the UK DFQF liberalisation offers, but can maintain MFN rates on a certain number of products imported from the UK.

EPAs protect ACP countries’ most sensitive local – mostly agricultural, but also industrial – products. While some are completely exempt from liberalisation, others are subject to certain quantitative limits, or reduced tariff rates.

Rules of Origin

To encourage regional integration and the development of regional value chains, RoO in EPAs allow for more extensive use of foreign components without losing free access to the UK market.

Tolerances - specified thresholds for products not meeting sufficiently transformation criteria - included in EPAs are more lenient than in other FTAs. Therefore, traders have more opportunities to benefit from preferences.

Moreover, cumulation provisions in EPAs (bilateral, diagonal, and full) expand the choices of traders to incorporate inputs from signatory countries and other neighbouring developing countries to benefit from preferences granted by EPAs.

EPAs’ derogation provisions may also grant derogation from RoO by applying more relaxed criteria to specific products originating in specific countries under specific conditions. Just to cite one example, preserved tuna and tuna loins under the UK-ESA EPA are entitled to such derogation [12].

Sector specific provisions

EPAs also contain sector-specific provisions for key economic resources in ACP states. Fisheries, for example, are considered an important source of food and foreign exchange for ESA countries. In the UK-ESA EPA, the parties agree to cooperate for the sustainable development and management of the fisheries sector in their mutual interest, taking into account the economic, environmental, and social impacts as well as support national and regional policies aimed at increasing the sector’s productivity and competitiveness[13]. Particularly, with regards to marine fisheries, in the UK-ESA EPA, the UK is committed to contributing towards mobilizing resources for fisheries management, conservation issues, vessel management, post-harvest arrangements, financial and trade measures, development of fishery products and marine aquaculture to ensure the sustainable exploitation and management of fisheries resources.

In addition, EPAs include additional provisions to further reduce time and cost of trade. Unfortunately, ‘modern trade issues’ have not been included in all EPAs, apart from the most comprehensive one with the CARIFORUM region. However, the agreements leave room for signatories to elaborate on these increasingly pertinent issues in the future.

Regional integration

Regarding regional integration, EPAs contribute by joining up smaller markets into larger EPA regions. Regional preference clauses in EPAs set out that countries in the same region provide at least the same advantages to each other as they do to the UK. Furthermore, while many ACP countries maintain barriers amongst themselves, EPAs, coupled with other support initiatives for regional integration, will help them come to grips with technical and policy aspects of economic integration[14].

More flexible RoO, notably their provisions on cumulation, derogation, tolerance, and generous thresholds for products to obtain originating status, mean that parties can more easily claim EPA originating status to take advantage of the liberal market access offered by the UK. This will contribute to economic development through export-led growth, but also foster regional value chains leading to further regional economic development.

Development

Trade and investment under EPAs are an important channel to boost economic growth and sustainable development in ACP countries. To further assist development via trade under EPAs, robust safeguards are provided to help protect domestic industries and local producers from disruptive effects. Bilateral safeguards provide for the possibility to limit trade temporarily when the imports of certain products take place in such a quantity or in such a way that poses a threat to domestic industries, or risks creating disturbances in an economic sector. Furthermore, to shield infant industries, tariffs may be reintroduced together with additional instruments to ensure adequate policy space for ACP countries in building their economies. In addition, EPAs also contain provisions on aid-for-trade measures, and encourage deeper cooperation on customs, technical barriers to trade (TBT) and sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) matters.

Beyond indirect impacts through enhanced trade and investment, EPAs’ annexes on development are expected to yield specific outcomes for developing partner states. The development chapters and commitments aim to provide targeted support to parties in their implementation of EPAs, which often take the Cotonou Agreement as a reference framework for economic development and poverty reduction. The ESA-UK EPA, for instance, sets out an indicative list of potential development targets that benefit African partner states via the development of infrastructure, key sectors, regional integration, trade policy, and institutions.

Other development objectives of EPAs are enshrined throughout the agreements’ provisions that seek to create new business, trade, and investment opportunities, generate positive impacts on the labour market, provide support for farmers, and promote regional economic integration. Among other things, by offering more legal certainty, EPAs are expected to attract UK investors into ACP countries, which will drive economic development and create new jobs [15].

The UK EPAs contain provisions on labour and environmental standards of varying degrees, with the CARIFORUM EPA often referred to as the model agreement for sustainable development [16]. EPAs lacking such provisions contain commitments on future negotiations.

Last but not least, EPAs reaffirm the parties’ commitments to upholding human rights, democracy, and rule of law as enshrined in the Cotonou Agreement, and refer indirectly to the possibility to suspend the agreements should these principles be violated (non-execution clauses).

Capacity building

The development matrix in the ESA-UK EPA provides several illustrative activities on capacity building. Examples include designing and constructing instruments to mobilise resources for investment; human resource development; service standards to facilitate trade and business transactions; information and communication technology-enabled services and institutional reforms to allow for integrated electronic information systems; and building sustainable production chains through harmonised regional policies, regulatory frameworks, and quality certification instruments accredited to international standards.

1.4. Benefits of UK EPAs

EPAs enable ACP countries to grow their economies in a sustainable way and raise their citizens’ living standards. The EU has highlighted ten benefits of the EU-EPAs for participating ACP states[17], which will apply equally in the context of the new UK-ACP EPAs.

- EPAs promote shared values

- In every EPA the UK and its partners agree to promote:

- labour standards.

- environmental protection.

- good governance.

- human rights.

- To put the EPAs into practice, various stakeholders from government authorities to business associations, NGOs and trade unions are involved.

- In every EPA the UK and its partners agree to promote:

- EPAs protect local producers

- EPAs enable ACP countries to protect their local producers that may otherwise struggle to compete against UK imports. ACP countries can opt to retain tariffs on sensitive goods. In case imports of some products suddenly surge, they can apply safeguard measures, such as quotas.

- EPAs encourage industrialisation

- EPAs help ACP countries produce and export higher-value processed goods instead of just unprocessed, lower-value commodities thanks to highly flexible RoO. For example, textile products can enter the UK duty-free if at least one stage of production, e.g., weaving or knitting, takes place in an EPA country.

- EPAs support ACP farmers

- EPAs assist ACP farmers in meeting the UK’s high standards in food safety and animal and plant health. EPAs also allow ACP countries to respond, for instance by banning imports of agricultural products from the UK, should problems arise.

- EPAs promote closer relations between neighbouring countries

- Regional EPAs build on the existing efforts of ACP countries to work more closely together and integrate their economies. EPAs also promote regional value chains because a country can process inputs from its neighbours and still benefit from duty-free access to the UK.

- EPAs help signatories respond together to global challenges

- In the past, the UK offered unilateral access to its market, which might be withdrawn at any time. By signing reciprocal EPAs, both sides make binding commitments to each other. EPAs also create joint institutions, enabling ACP countries and the UK to reach decisions together. EPAs may also come with UK development aid, which helps ACP countries to make the most out of the partnership.

- EPAs cut the costs of exporting and importing

- The UK provides aid-for-trade along with every EPA. This helps partner countries adapt their customs procedures and reduce paperwork, which results in less hassle for exporters and importers and greater incentive to tackle corruption.

- EPAs generate more and better jobs

- EPAs help ACP countries to compete, thereby helping them expand their economies. New industries spring up will create more jobs. EPAs also encourage governments to work with trade unions and NGOs to improve labour standards.

- EPAs help countries attract more investment

- EPAs are permanent, with no end date, giving local or foreign potential investors the long-term stability, they look for. EPAs also signal that partners involved are serious about attracting businesses and giving them good prospects to set up or expand.

- EPAs create new business opportunities

- Firms from countries covered by an EPA can freely export to the UK – no duties to pay at customs and no quotas for most products. They can also import the inputs they need, such as machinery or components, at lower prices.

1.5. Misconceptions of UK EPAs

EPAs have sometimes been labelled as unfair by some commentators who argue that EPAs open ACP markets to international competition at the expense of local businesses. Other critics have accused EU-ACP EPAs of diluting the negotiating power of developing ACP countries, leaving them as rule takers. The followings are some most common misconceptions held by opponents of EU EPAs and their counterarguments[18], which will apply equally in the context of the new UK-ACP EPAs.

#1: ACP countries have been forced into EPAs by EU/UK pressure

No. The pressure to sign EU-ACP EPAs came from the expectations of other WTO members, including non-ACP developing ones, that the EU and ACP countries would respect their commitments to make their trade relations WTO-compatible by 1 January 2007. Whereas, the need to maintain and strengthen economic ties between the UK and ACP countries after the UK’s withdrawal from the EU has necessitated the negotiations of UK-ACP EPAs.

#2: Countries that have signed EPAs will see their markets flooded with cheap UK imports

No. Under the terms of EPAs, the ACP countries are free to exclude a wide range of sensitive goods and sectors from liberalisation. UK companies export little to most ACP countries. The interest is to build integrated supply chains with ACP countries that can be mutually beneficial.

#3: By signing EPAs with different ACP countries the UK has undermined regional integration

No. EPAs are designed to enhance the creation of regional value chains and support increased trade between all parties, including ACP countries. This is supported, for example, by flexible rules of origin.

#4: Cuts in import duties as ACP countries liberalise will undermine government revenue

No. ACP countries have excluded many products from liberalisation and will gradually liberalise other tariffs over 10-15 years, lowering tariffs on the imports that ACP economies need first. This will prevent dramatic changes in revenue. In addition, the UK is ready and has the means to assist ACP countries with fiscal reform and adjustment to help cushion any net fiscal losses observed as a result of EPAs.

#5: Future development funds are conditional on the signing of EPAs

No. Both the EU and the UK never tie development finance to the signing of EPAs. The regional financing element of the European Development Fund (EDF) does support ACP regional integration but its programming guidelines do not specify that this must involve an EPA. It states only that where there is an EPA, funds must support the smooth implementation of any related commitments. This is also the same approach of the Foreign & Commonwealth Office and the Department for International Development on funding for the EPA Support Programme[19].

#6: The UK is still insisting on negotiating on issues such as investment and services in full EPAs, even where ACP countries do not want to do so.

No. The UK has never insisted that these issues be covered by EPAs. But it believes that there are good development reasons explaining why they should be. Services like telecommunications, banking and construction are the backbone of a growing economy and most ACP countries desperately need to attract foreign investment in these sectors and others.

#7: EPAs are a danger to ACP countries’ development[20]

No. The UK's trade and development policy is more concerned on how the UK can use trade to help ACP countries build stronger economies and break their dependence on trade preferences and basic commodity trade. EPAs that the UK signs with ACP countries are designed to help bring greater opportunities to local businesses, attract new investment and build strong regional markets that can compete globally. EPAs will turn a trade relationship that is dependent on several commodities into one based on economic diversification and growing economies.

#8: RoO in EPAs bind countries to trade more with party states

The claim here is that RoO are too restrictive as they bind EPA countries to trade more with other EPA partners at the expense of third party LDC countries. However, countries are not bound, but rather have more liberal criteria for goods coming from EPA party states.

#9: Goods originating in the EPA states are good and goods from elsewhere are bad

While EPAs include chapters on TBT and SPS, it does not mean that all other goods are substandard. The quality of products is all gauged according to the same standards, it is up to trading firms to judge if certain products meet their needs and if the standards and certification are trustworthy.

#10: Imports from all ACP countries can enter partner states free of duty

Not all ACP states have FTAs with one another. Treatment of goods from ACP states is thus decided on the trading relationship between the country of import and the originating country.

Beyond capacity building with specific development objectives, EPAs also involve enhanced policy cooperation and dialogue on agriculture and food security that, among other things, seek to improve farmers’ capacity to comply with SPS and other agricultural standards. Furthermore, EPAs also attempt to address capacity relating to issues at the border. For example, several UK-ACP EPAs with ESA, SACUM, CARIFORUM, and Pacific States provide a legal framework with clear trade facilitation objectives.

Finally, programmes to take advantage of or support the implementation of EPAs will be carried out to improve ACP countries’ technical and administrative capacity in both the public and private sectors.